Science

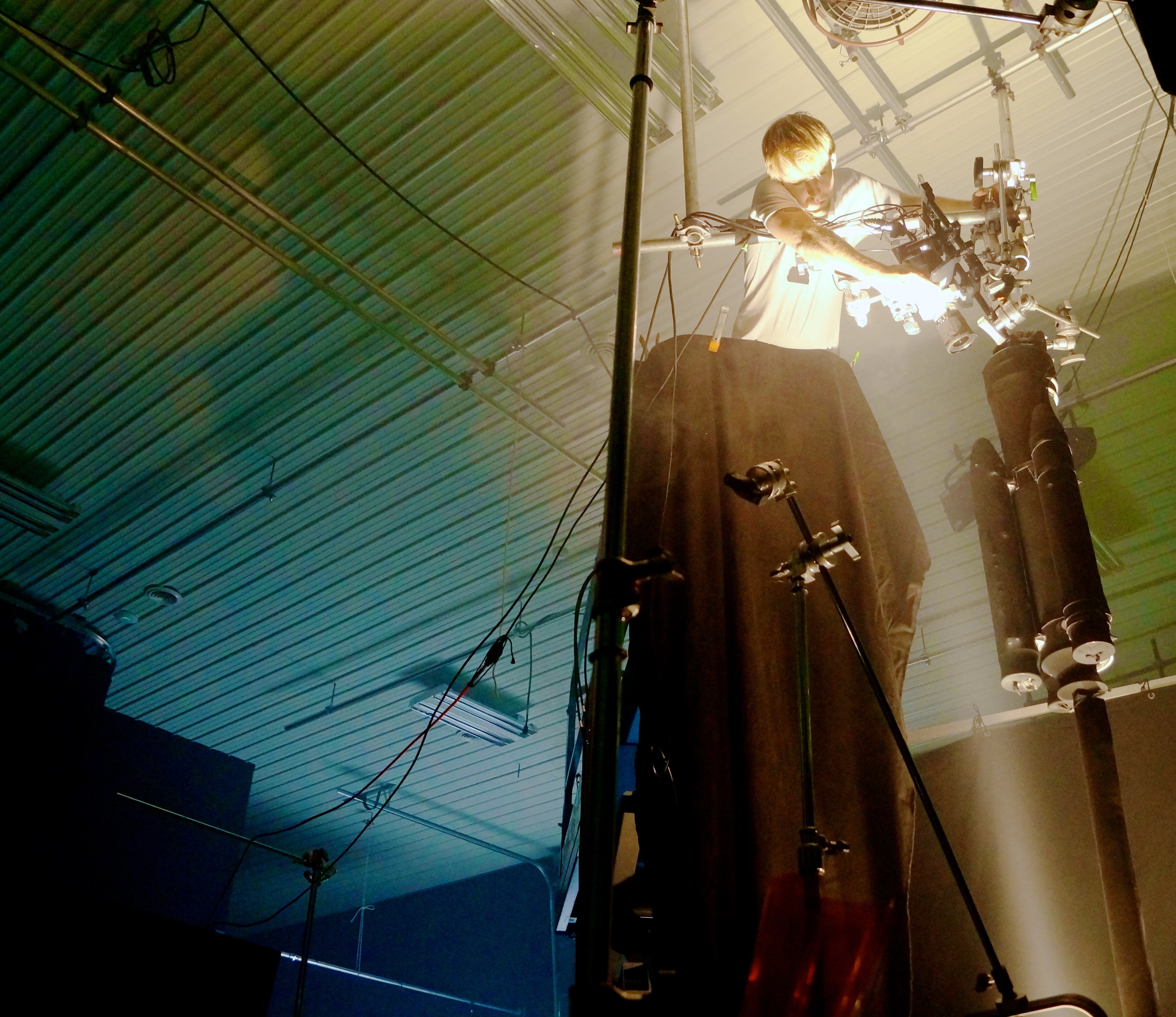

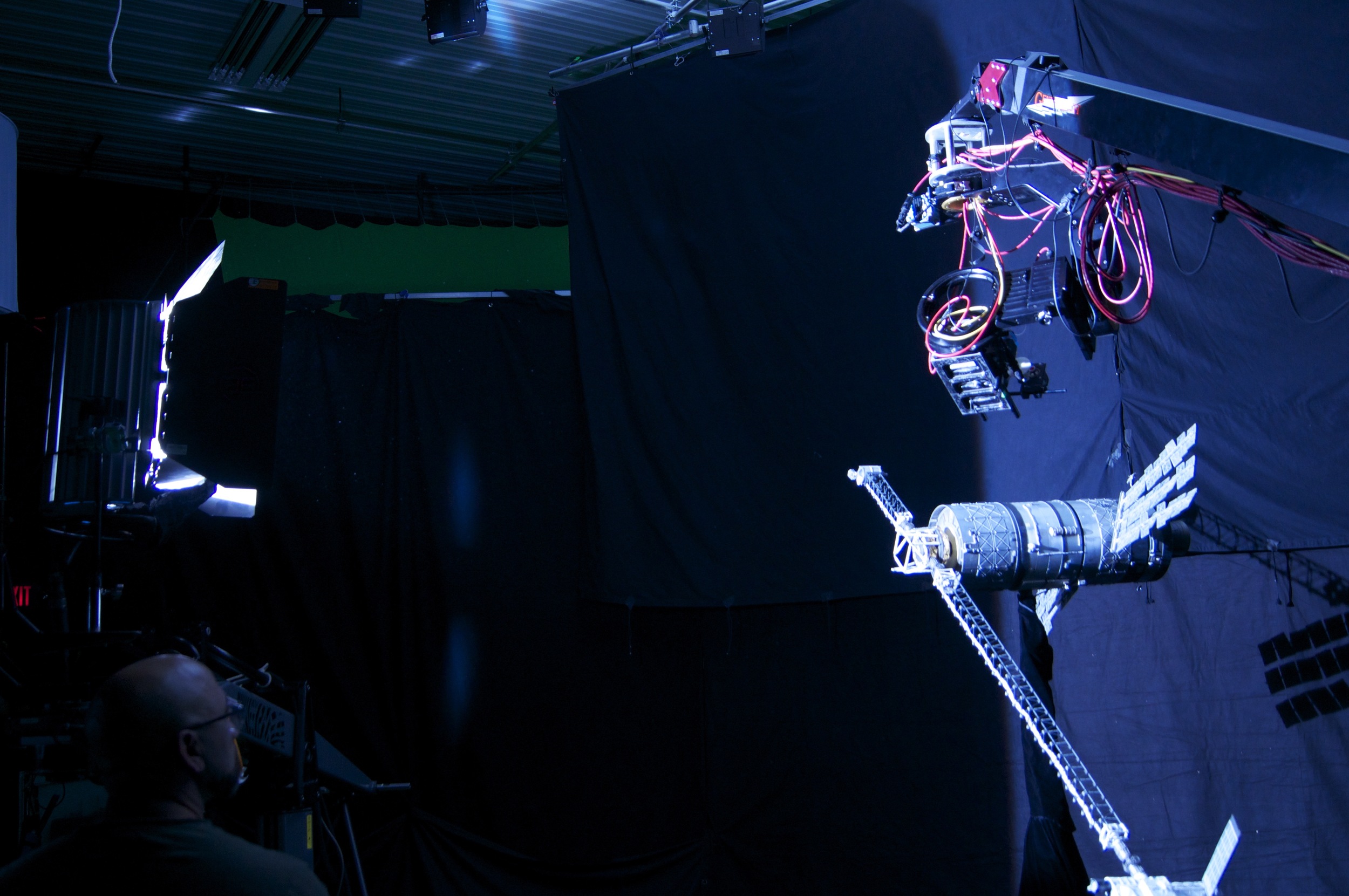

Although set on a ship using technology that is conceptually feasible in the realistic near future, I wanted the film to go beyond the literal experience of a journey in space. My concerns scientifically were to be as accurate as possible, while still creating the emotional, intellectual and dramatic scenarios I wanted to address.

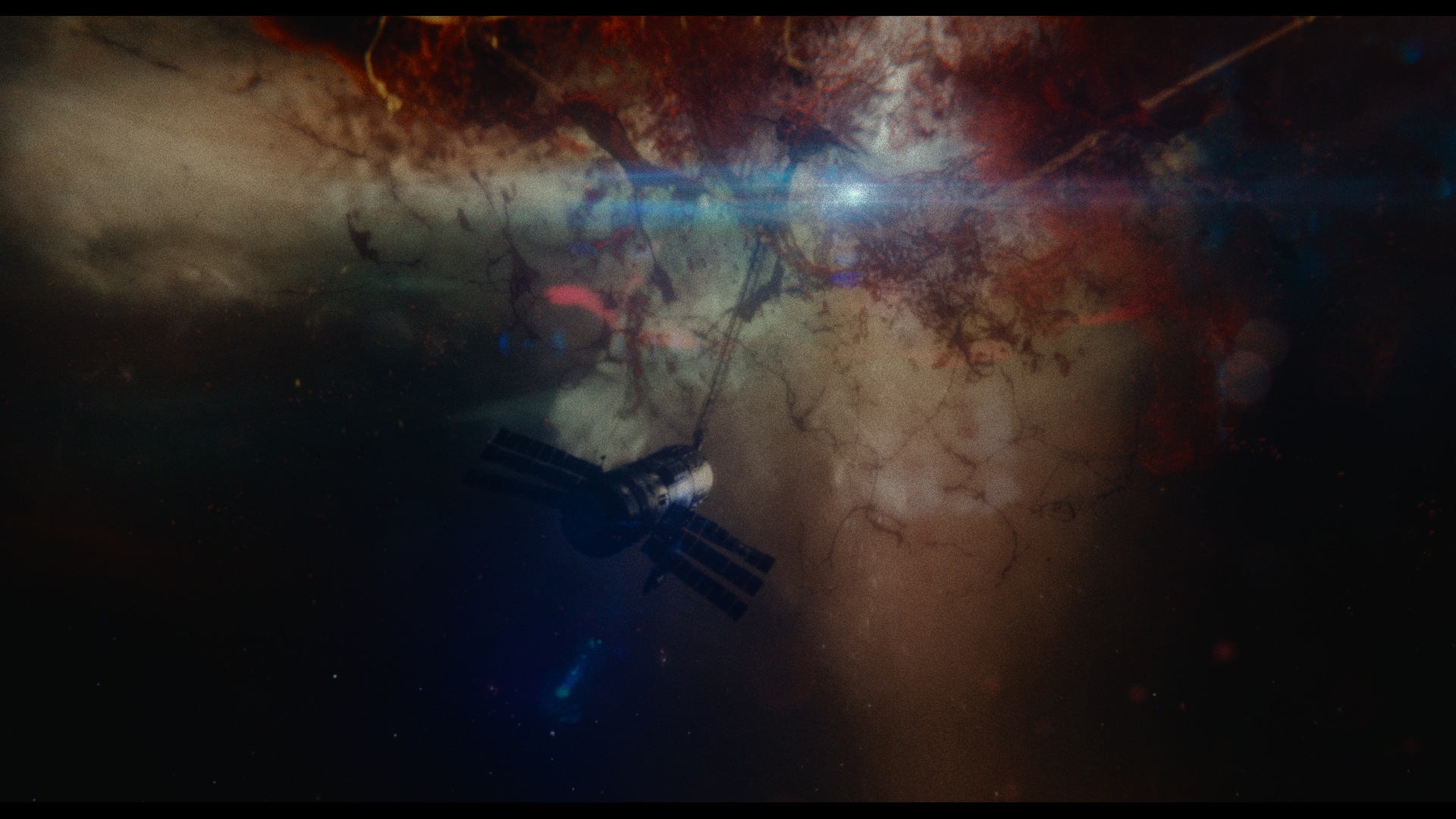

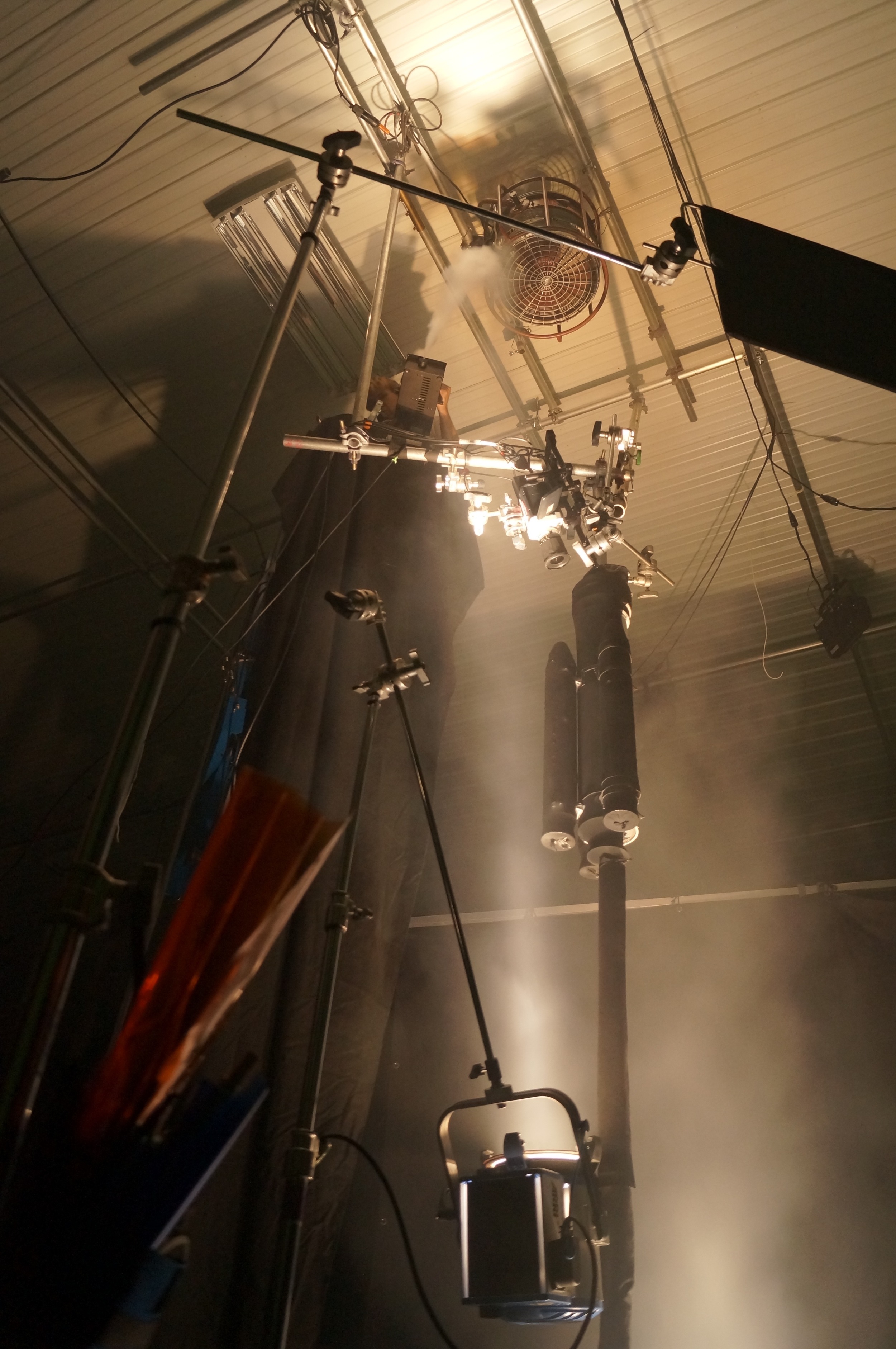

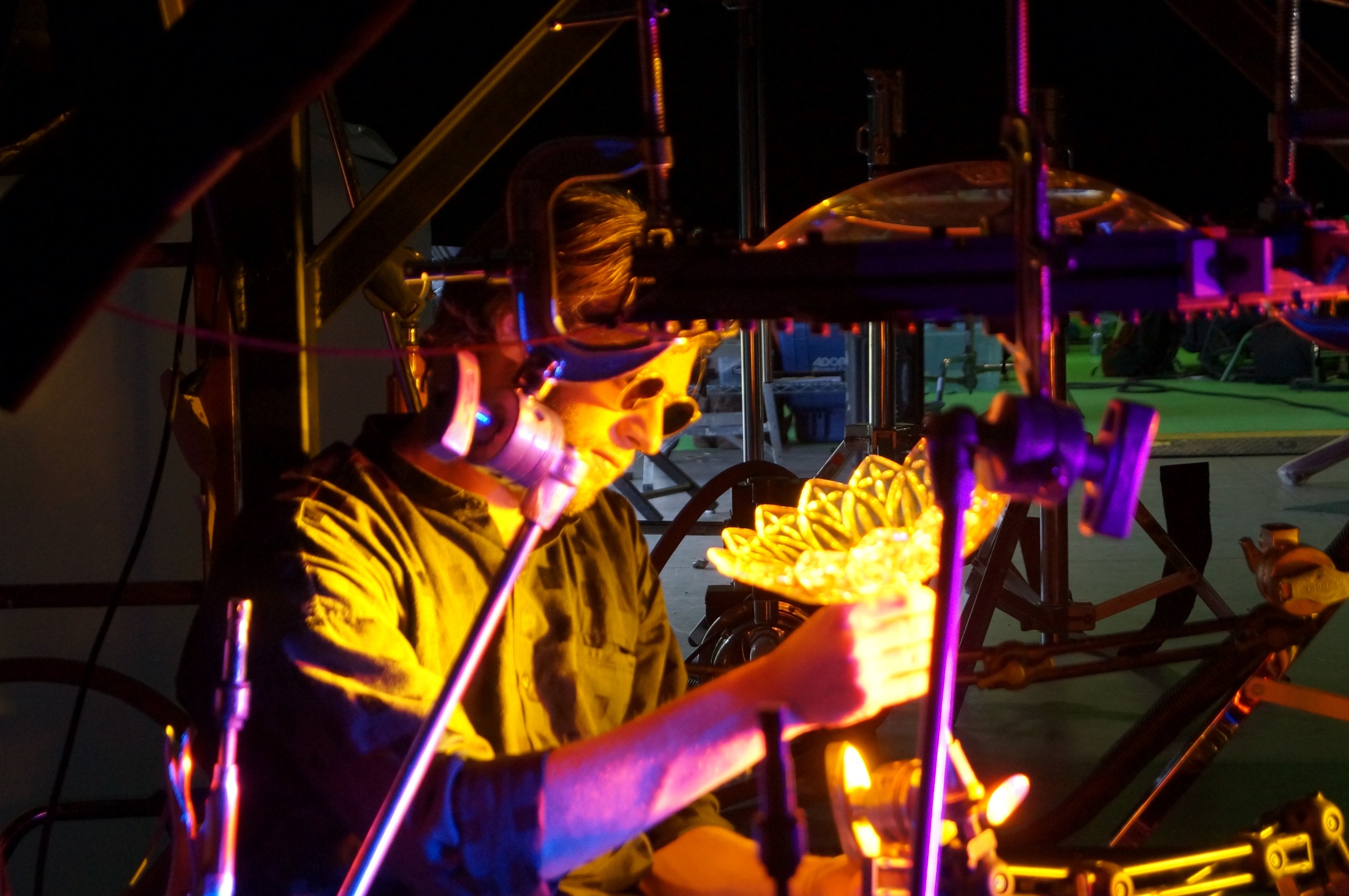

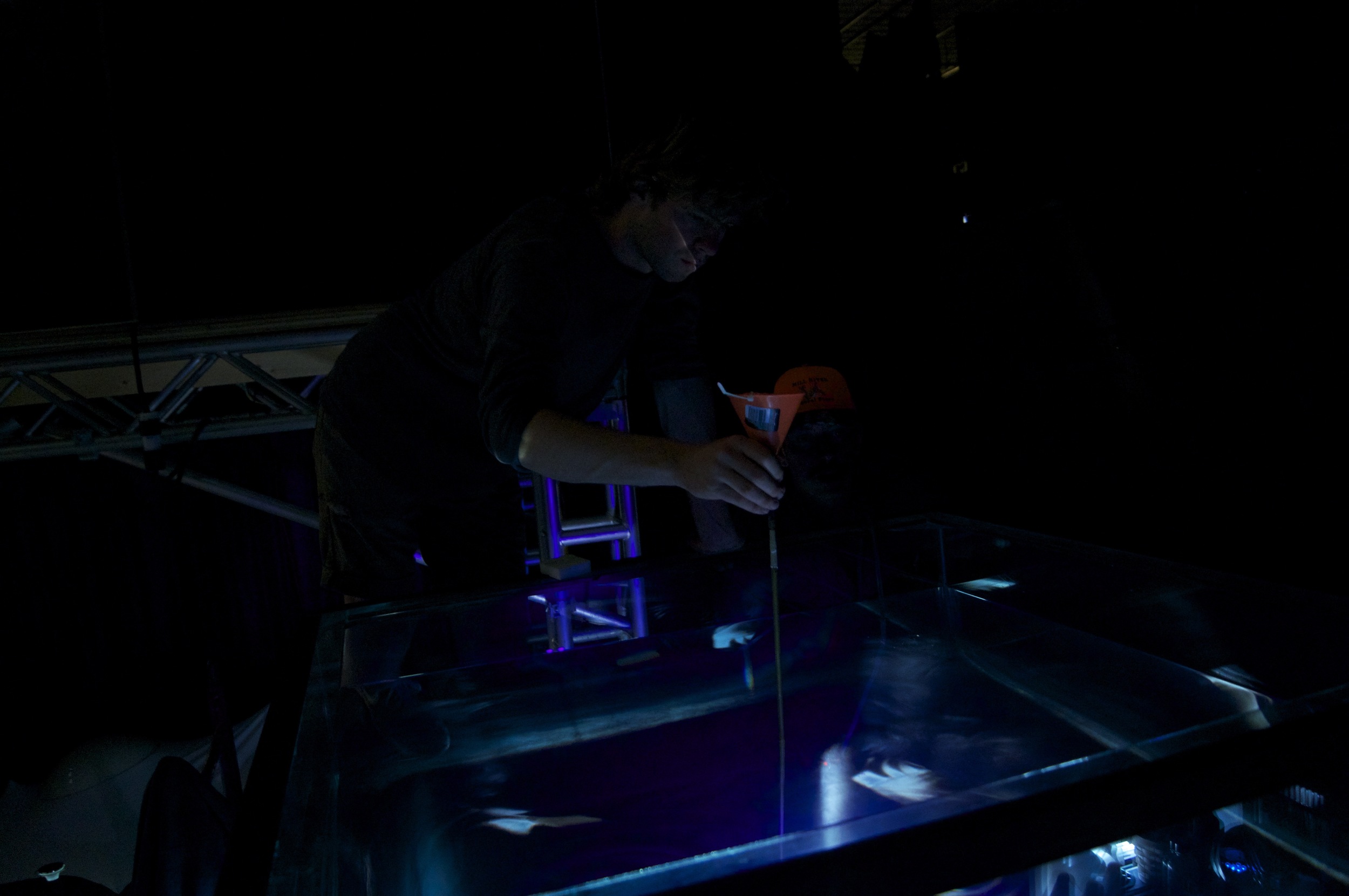

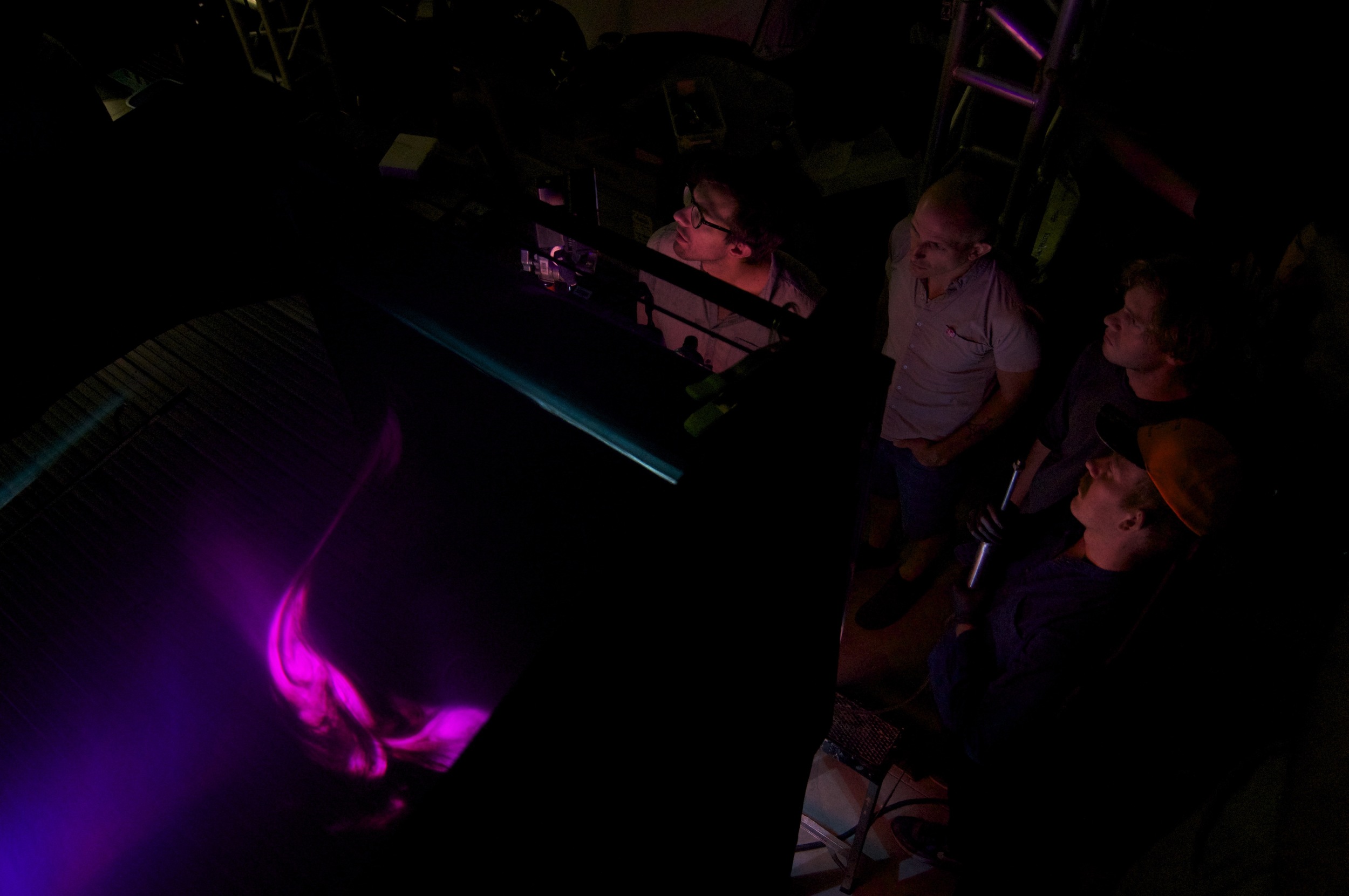

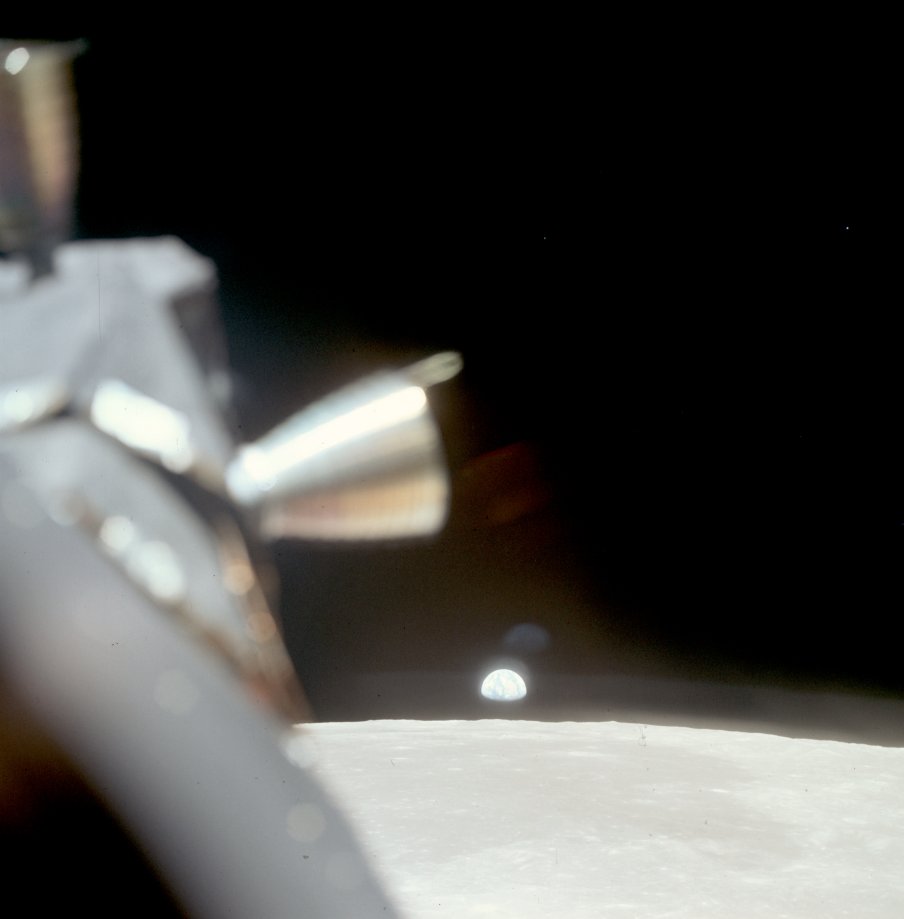

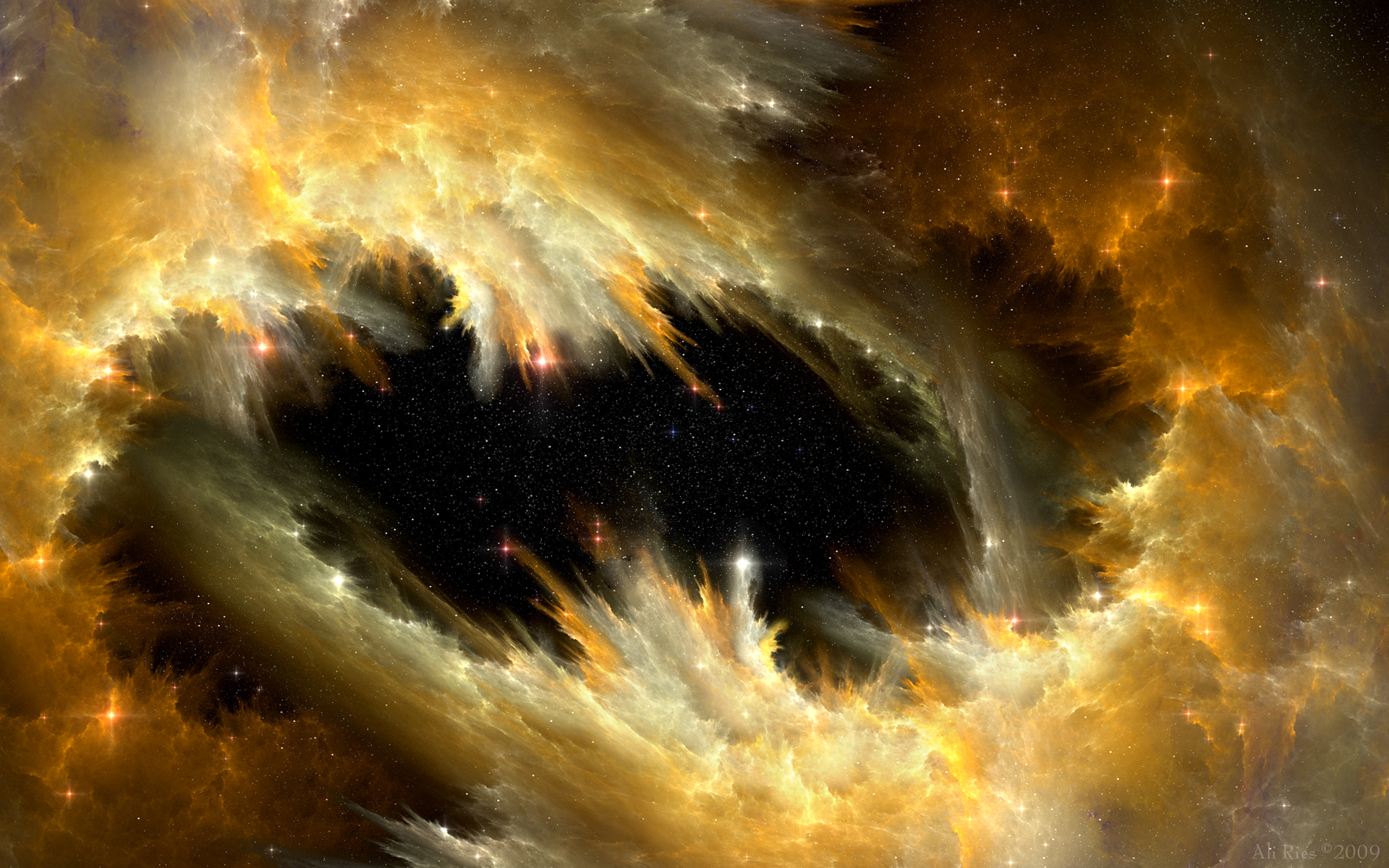

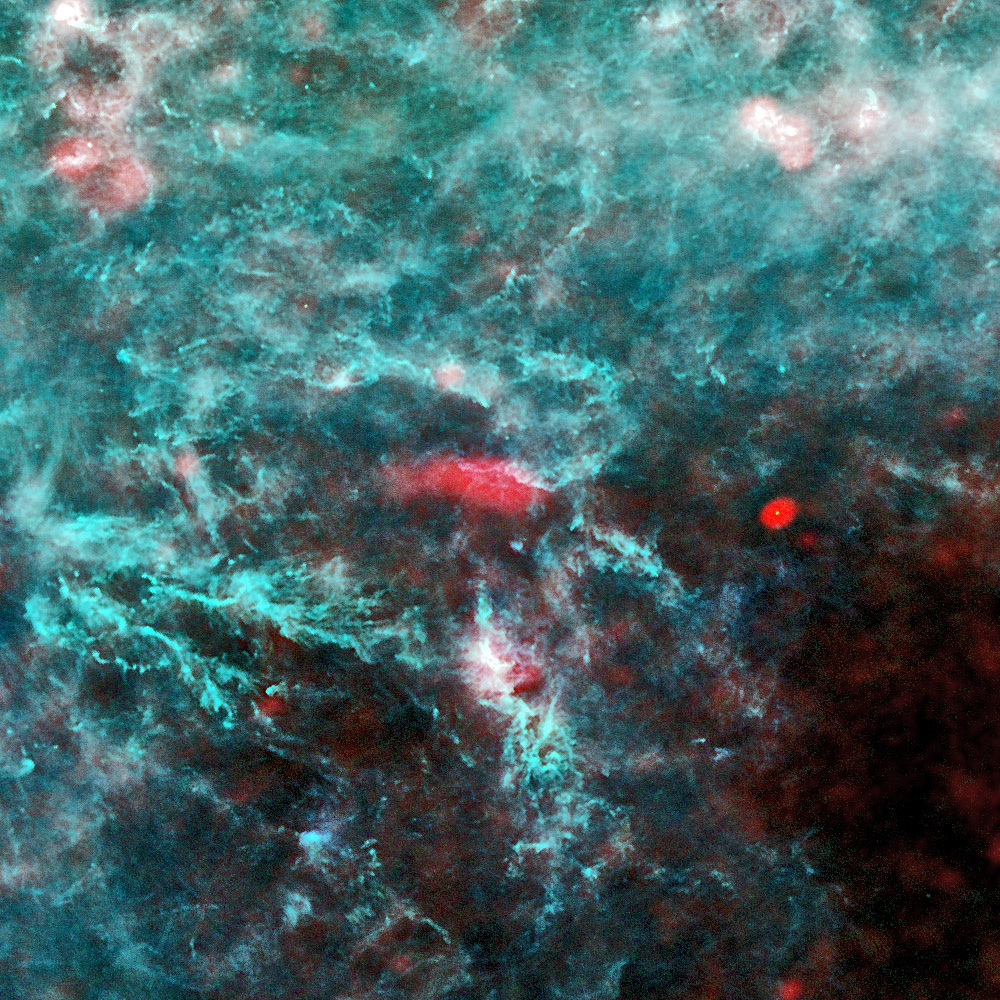

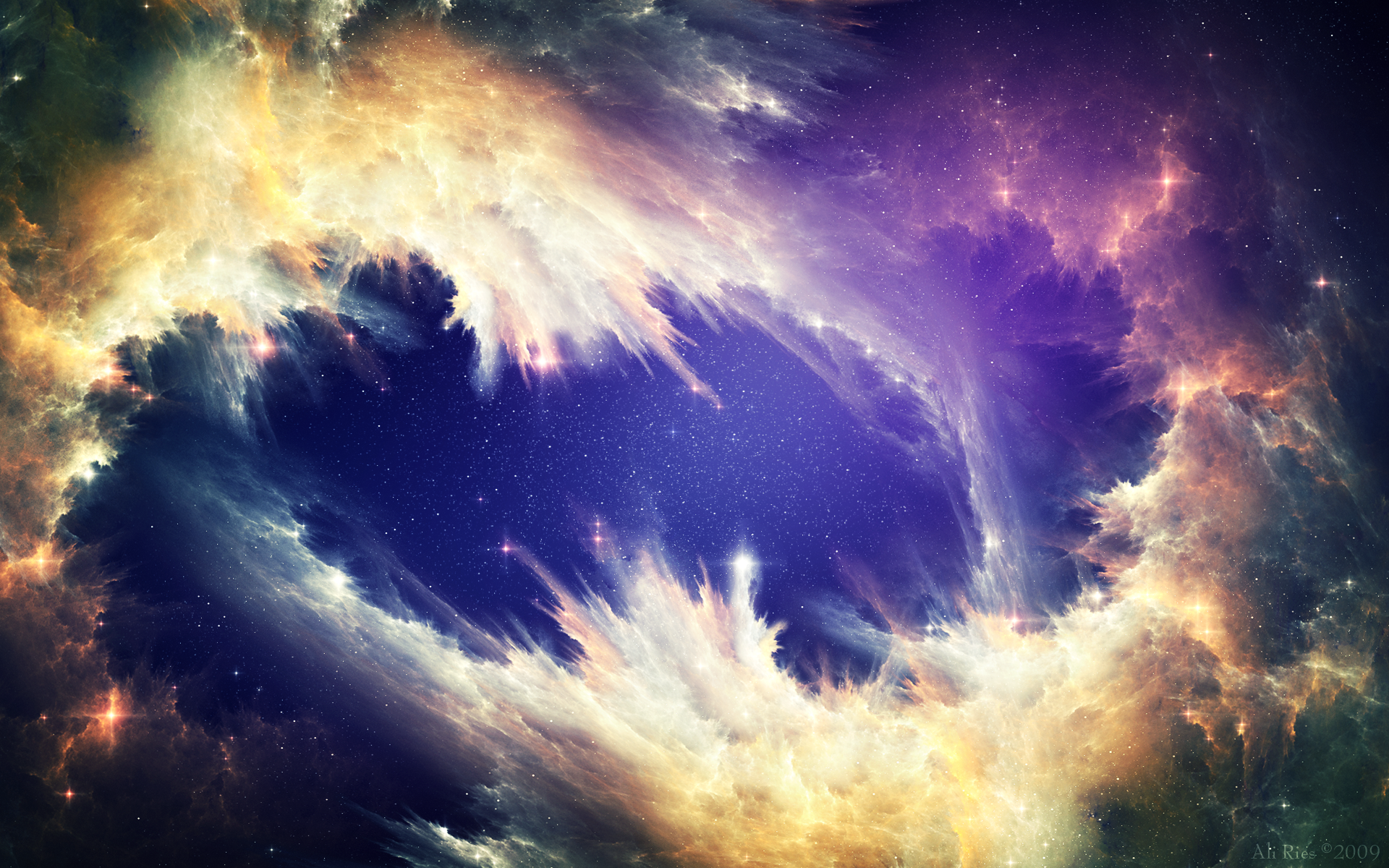

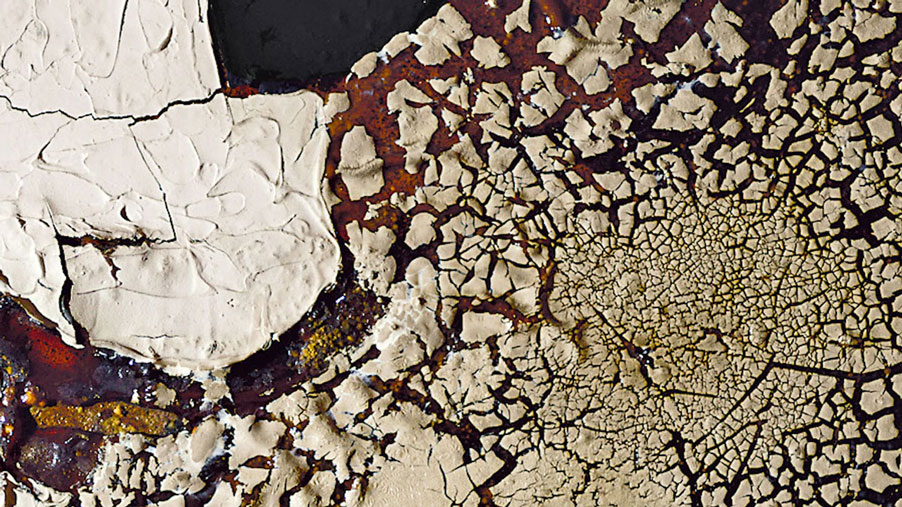

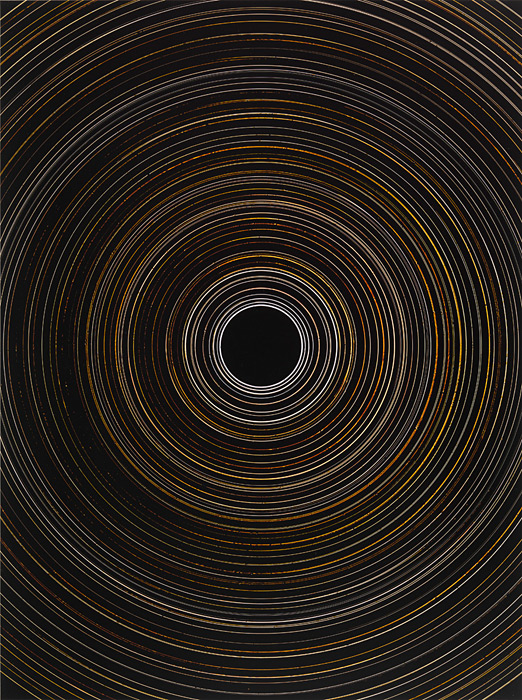

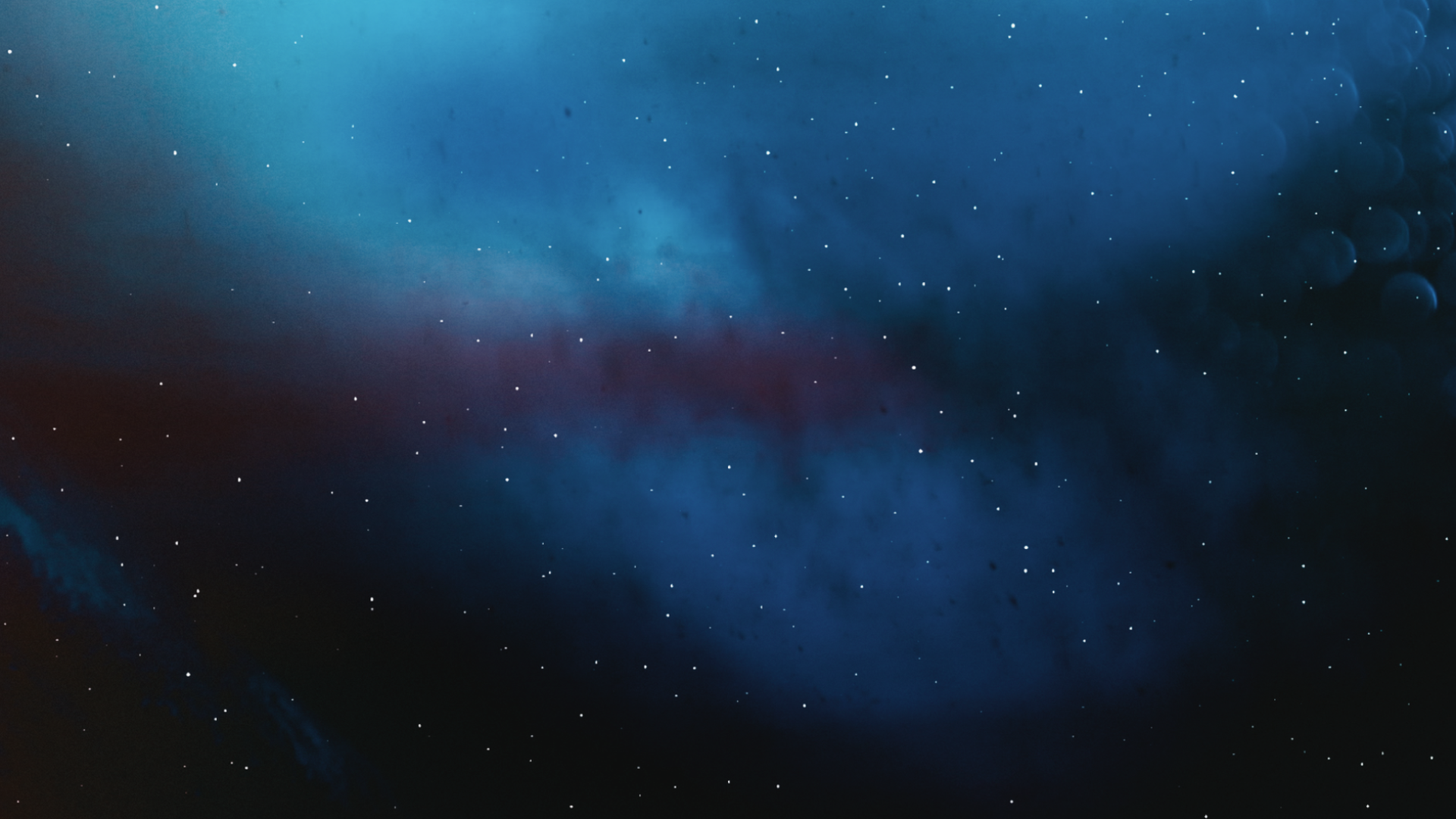

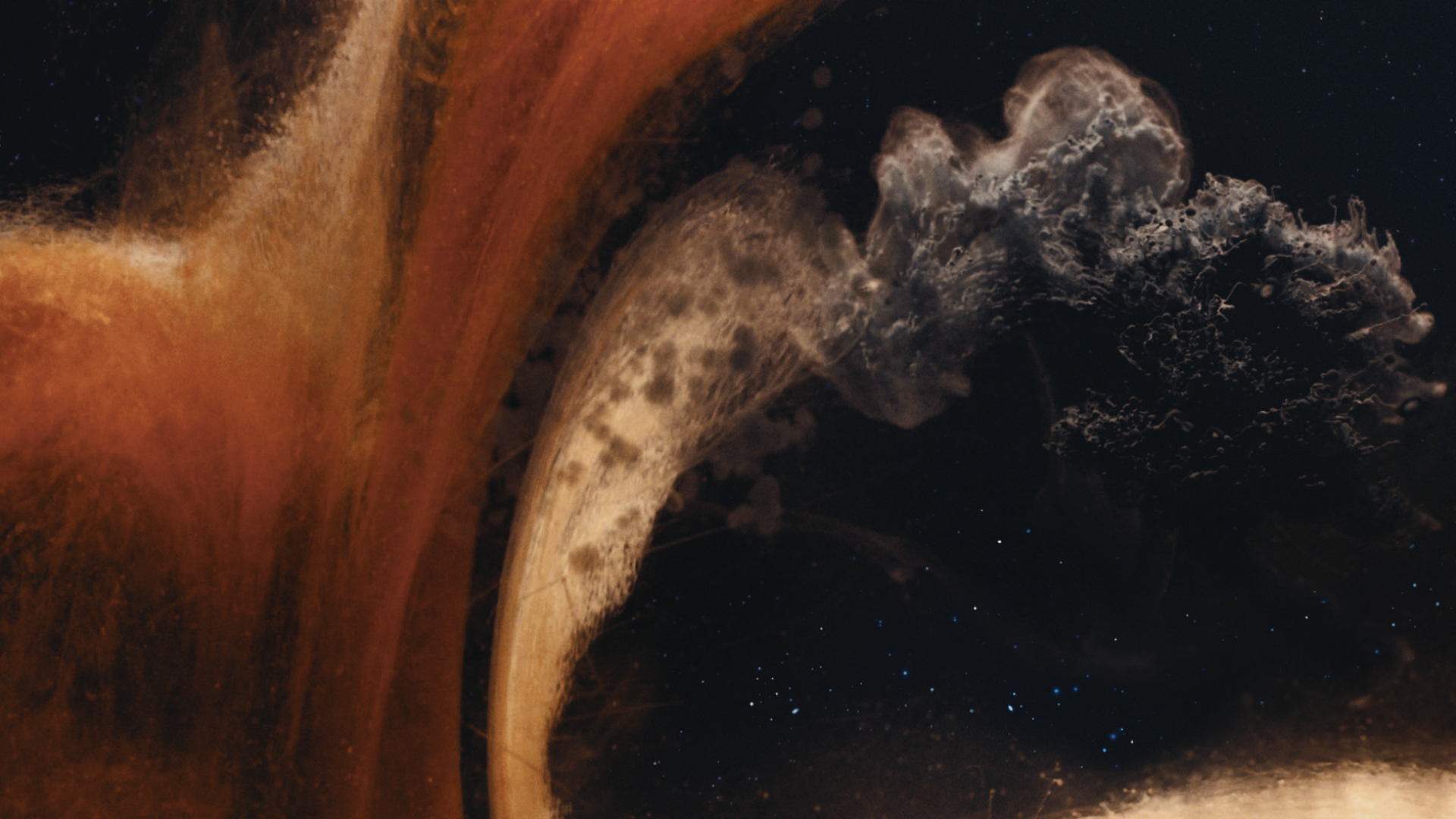

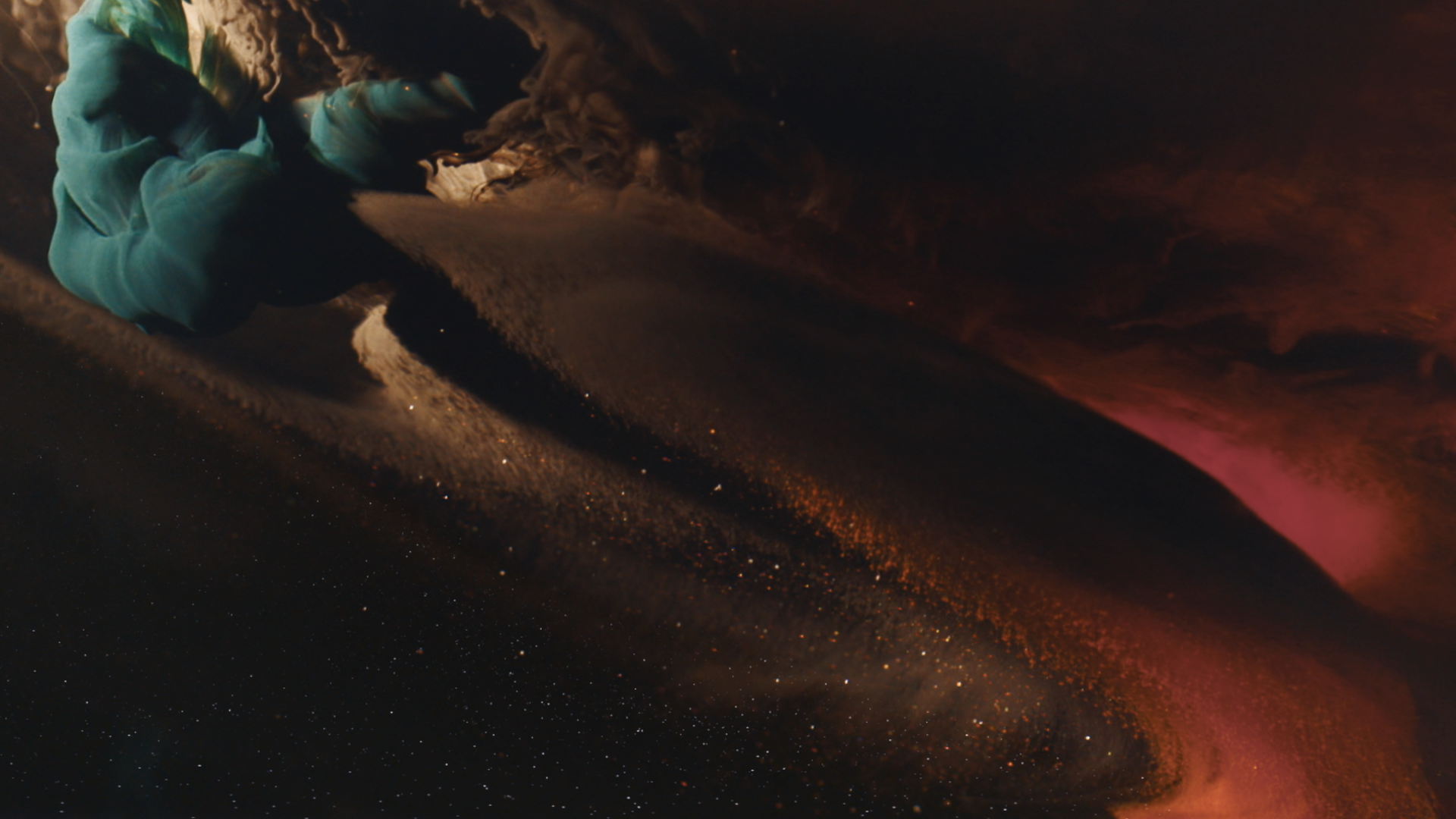

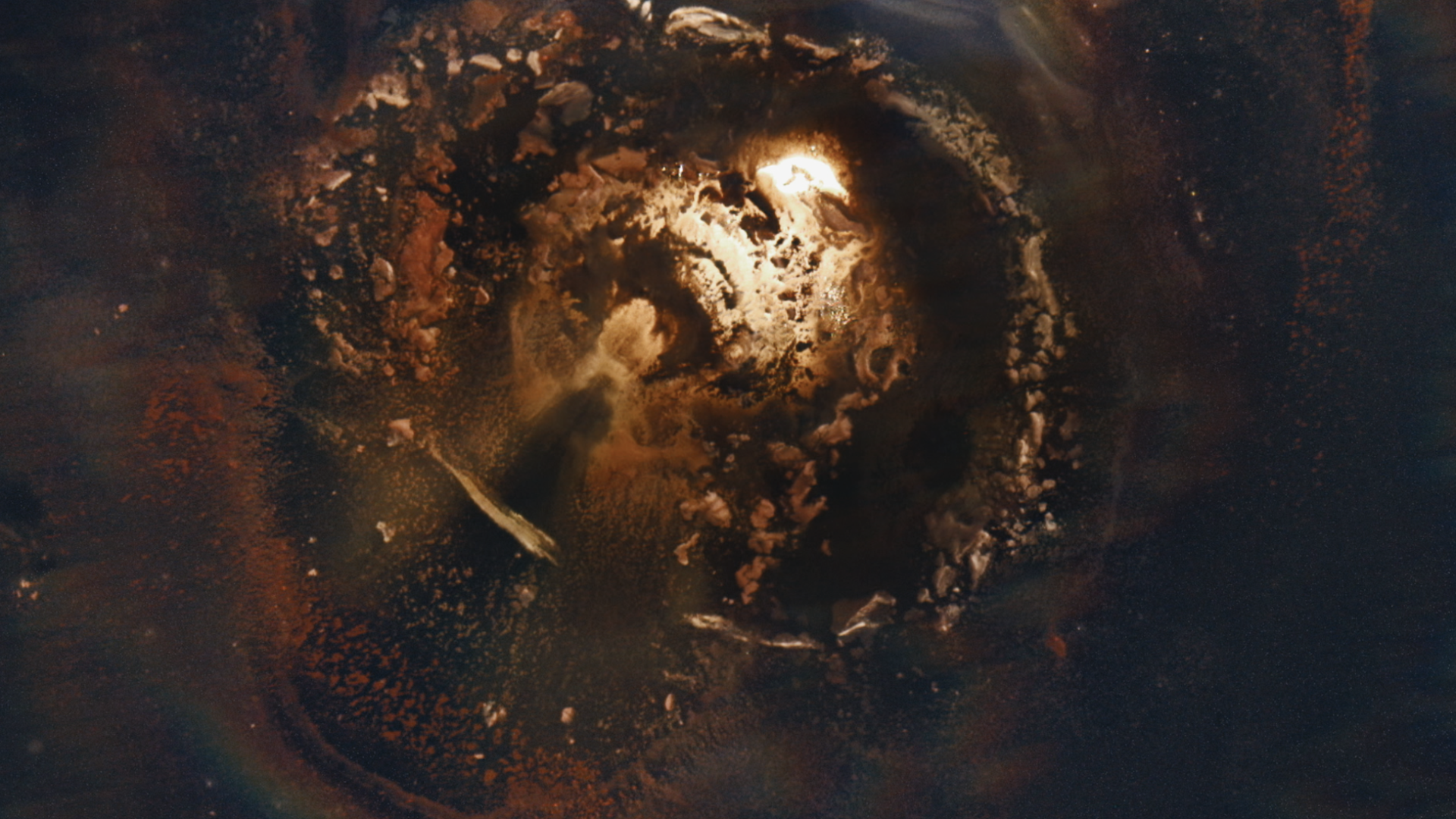

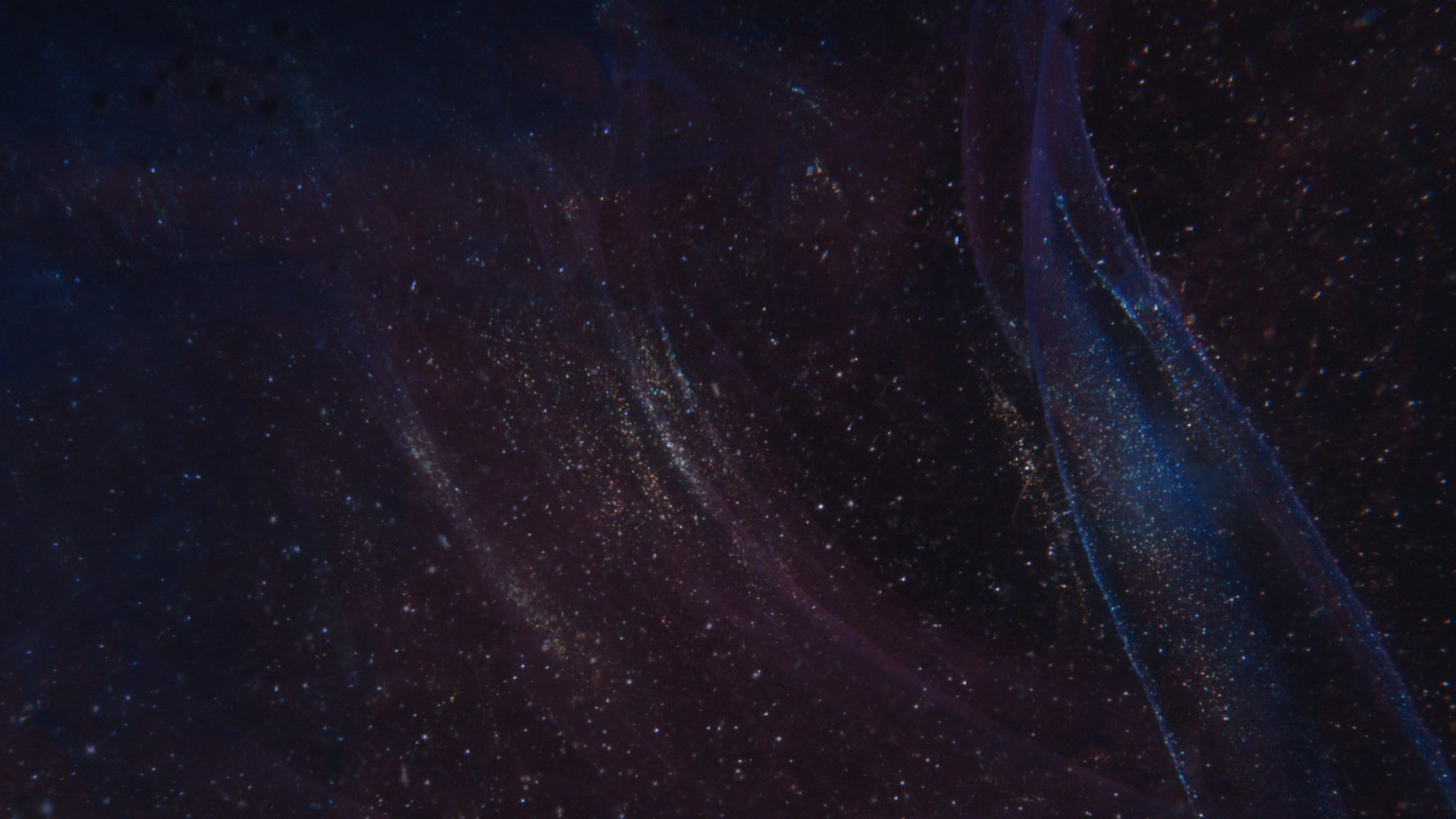

Perhaps the most important place where we made an artistic digression from the literal is in the view of space itself--in our movie it has texture and color. What we created is not unlike some of the images you might see from the Hubble telescope, showing the light and magnetism of multiple galaxies, only we created that same look relatively small distances in space, between Earth and Mars. This was important to me because the only way I could comprehend being in deep space would be like being deep in the ocean: it’s vast and dark and deadly and seemingly empty, but of course it’s also filled with bacteria and minnows and whales and quarks and comets and planets. To understand the ocean, even if you’re in it, you need to imagine it. So Stanaforth’s experience of space must likewise be subjective. At the beginning of the movie, we present a more traditional, literal outer space: blackness with tiny white stars; by the end of the movie, Stanaforth is moving through a maelstrom of viscous chaos. It’s not realistic, but neither is it imaginary.

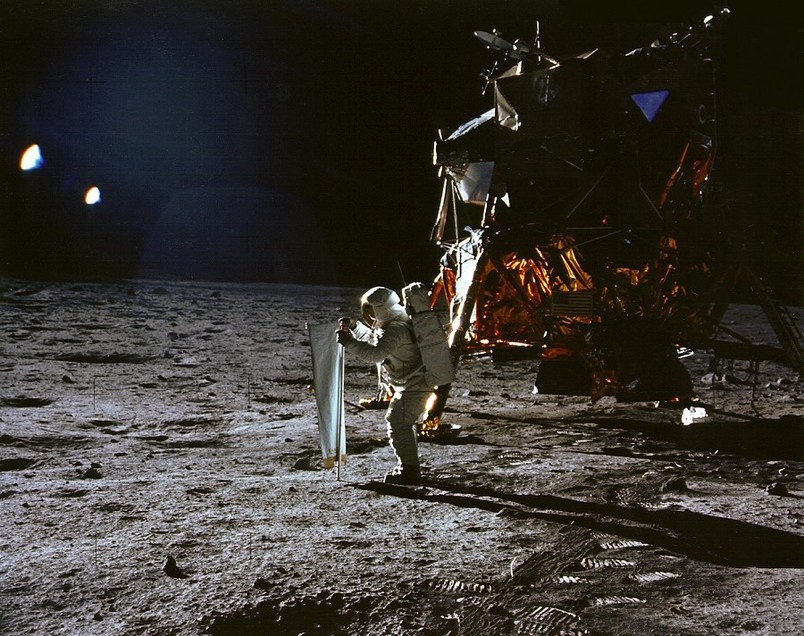

Various international space agencies have studied missions designed for solitary astronauts, for reasons ranging from cost to personal dynamics. It remains unlikely that there would be solo missions any time soon, but for my story, I thought the issues I wanted my character to confront—his willingness to be isolated from humanity for the sake of humanity; his awareness of his marginal power in the face of the vast universe—I thought it would be more interesting if he was alone.

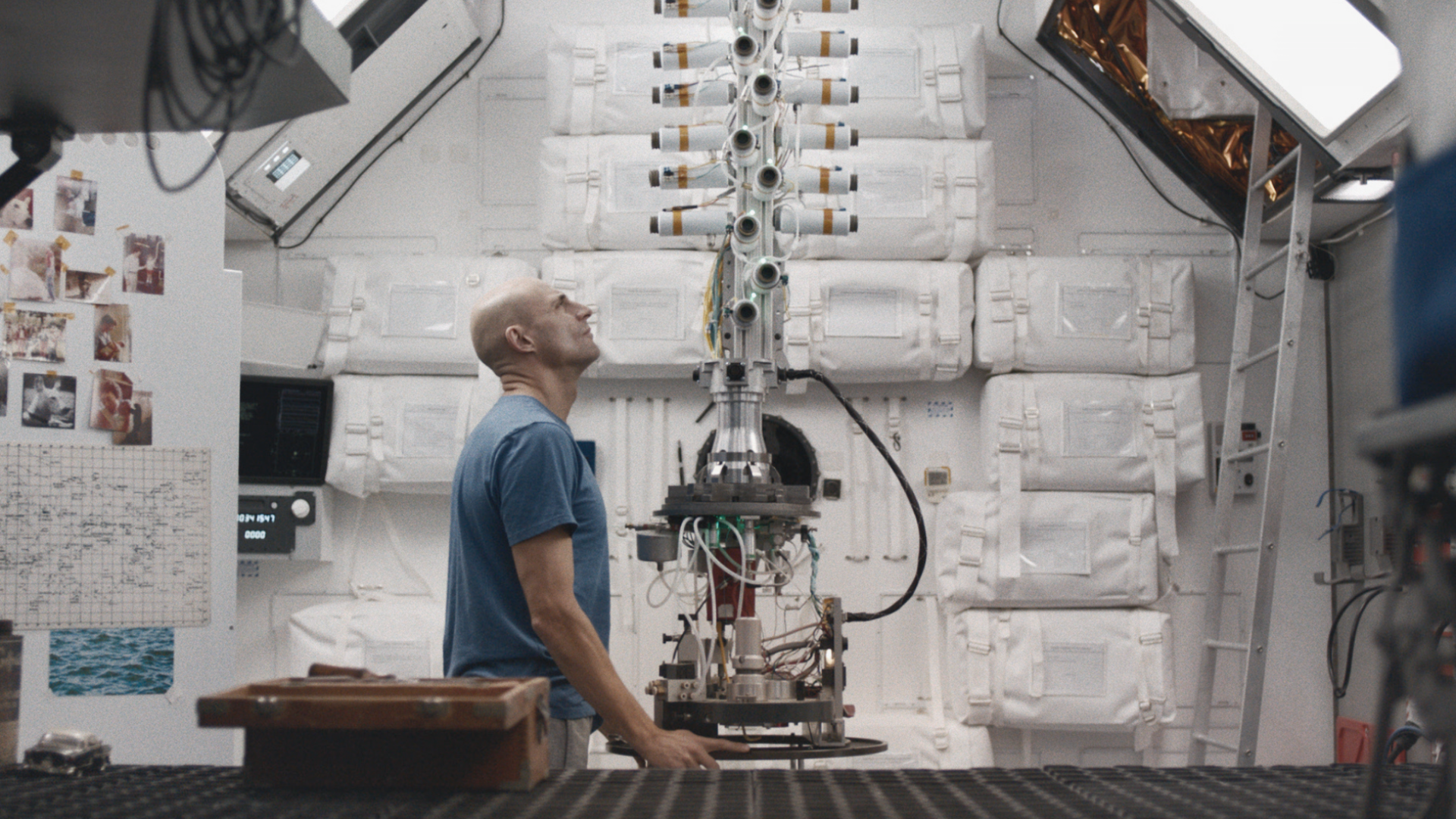

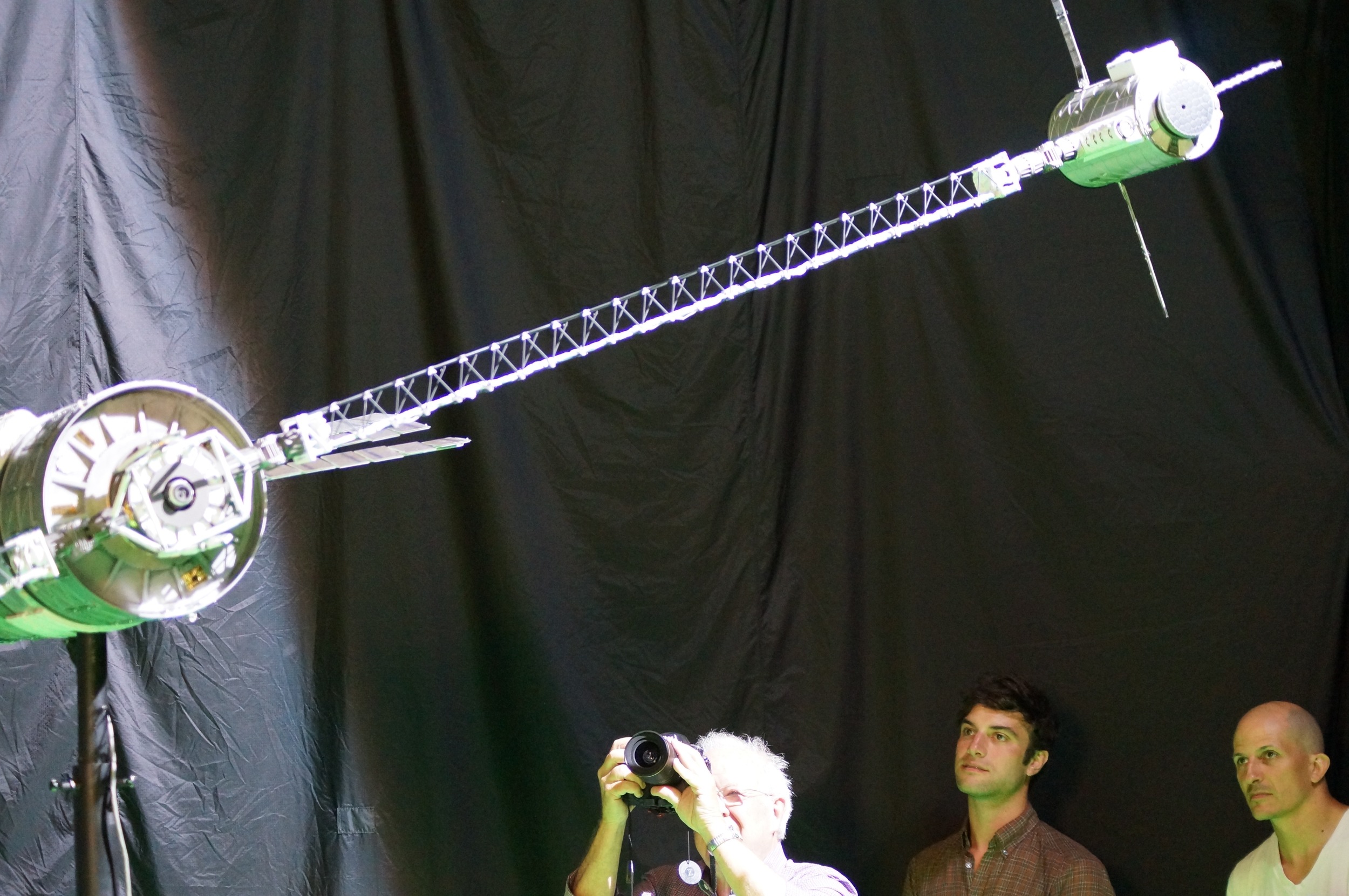

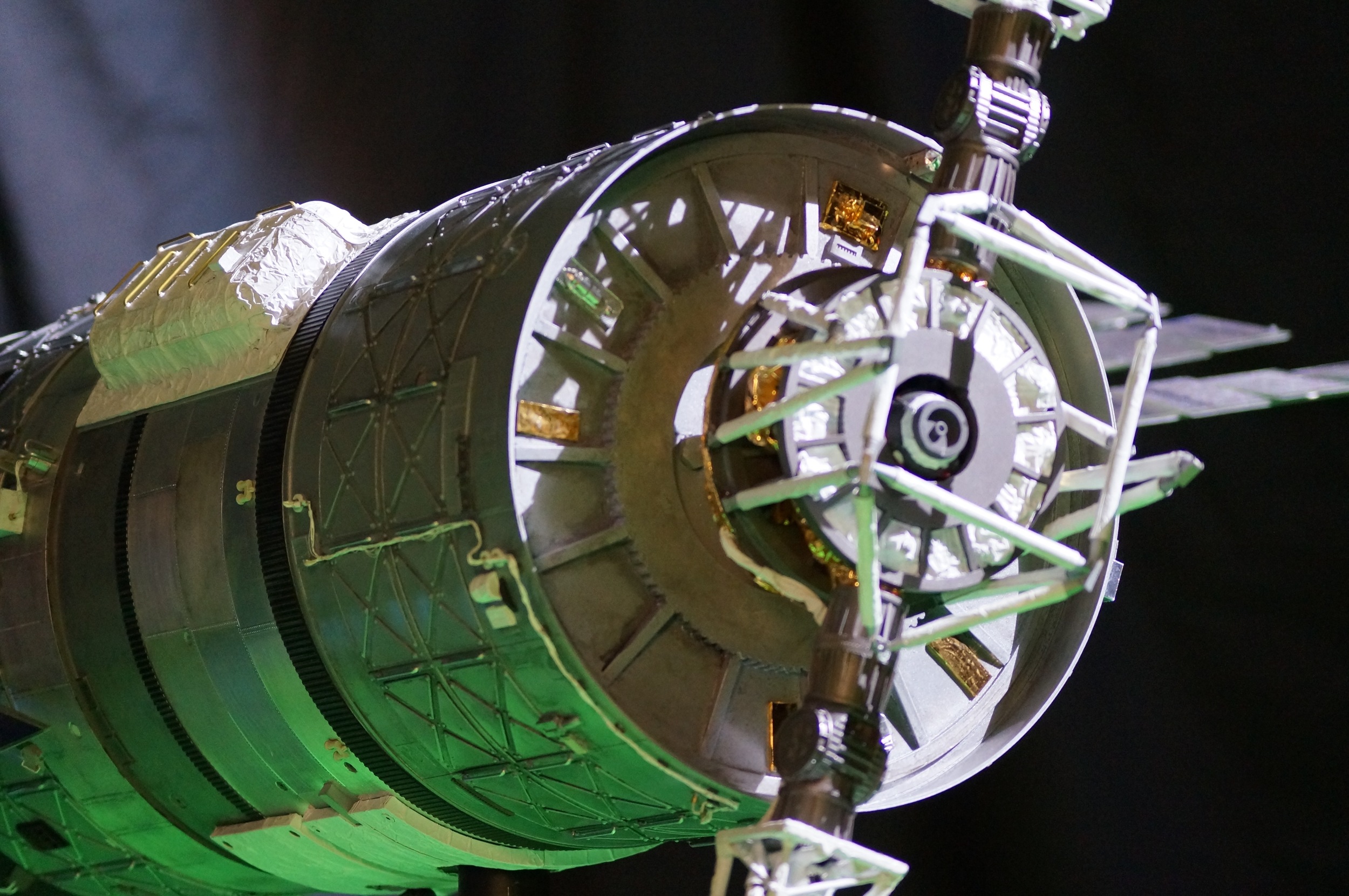

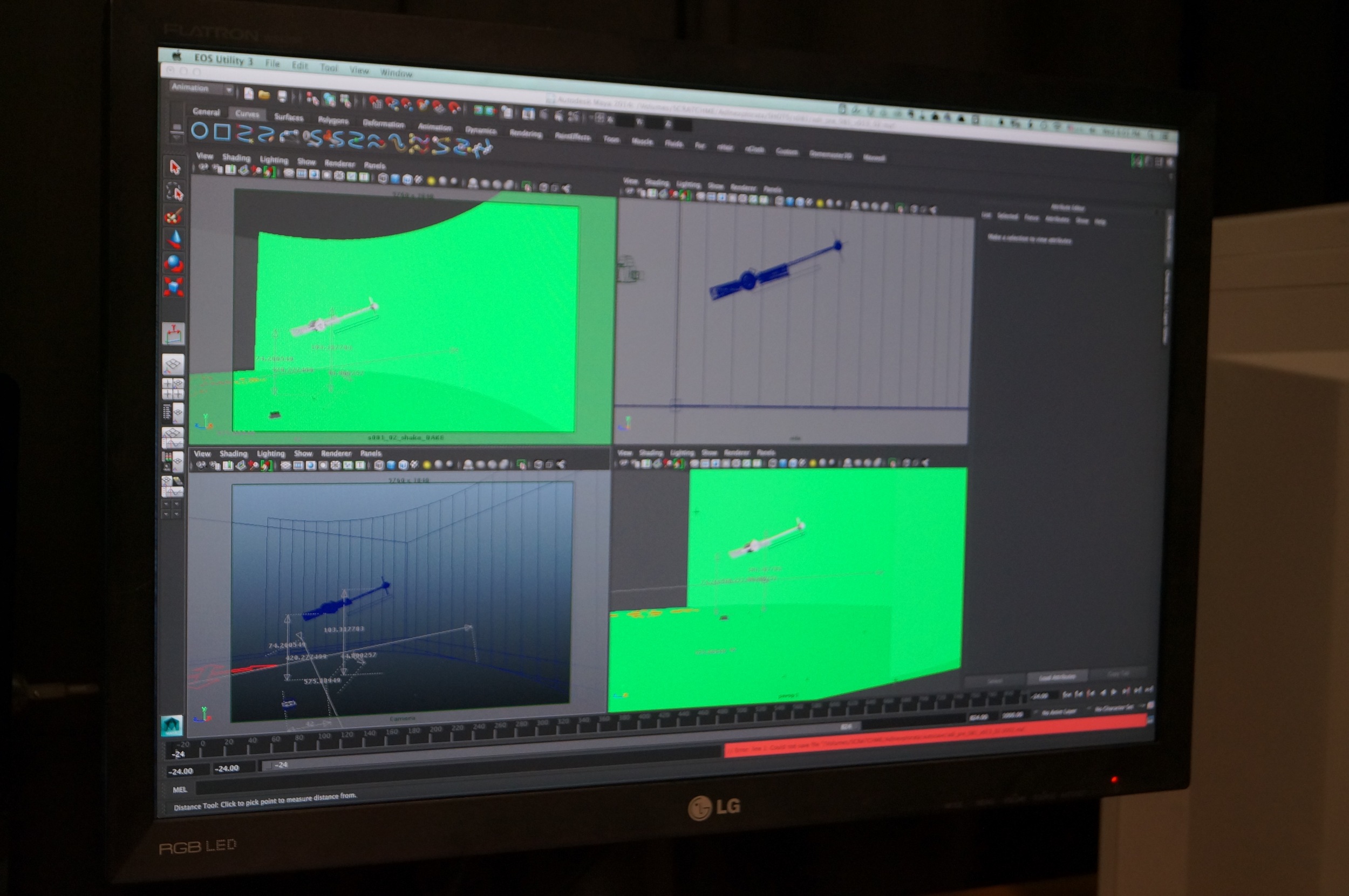

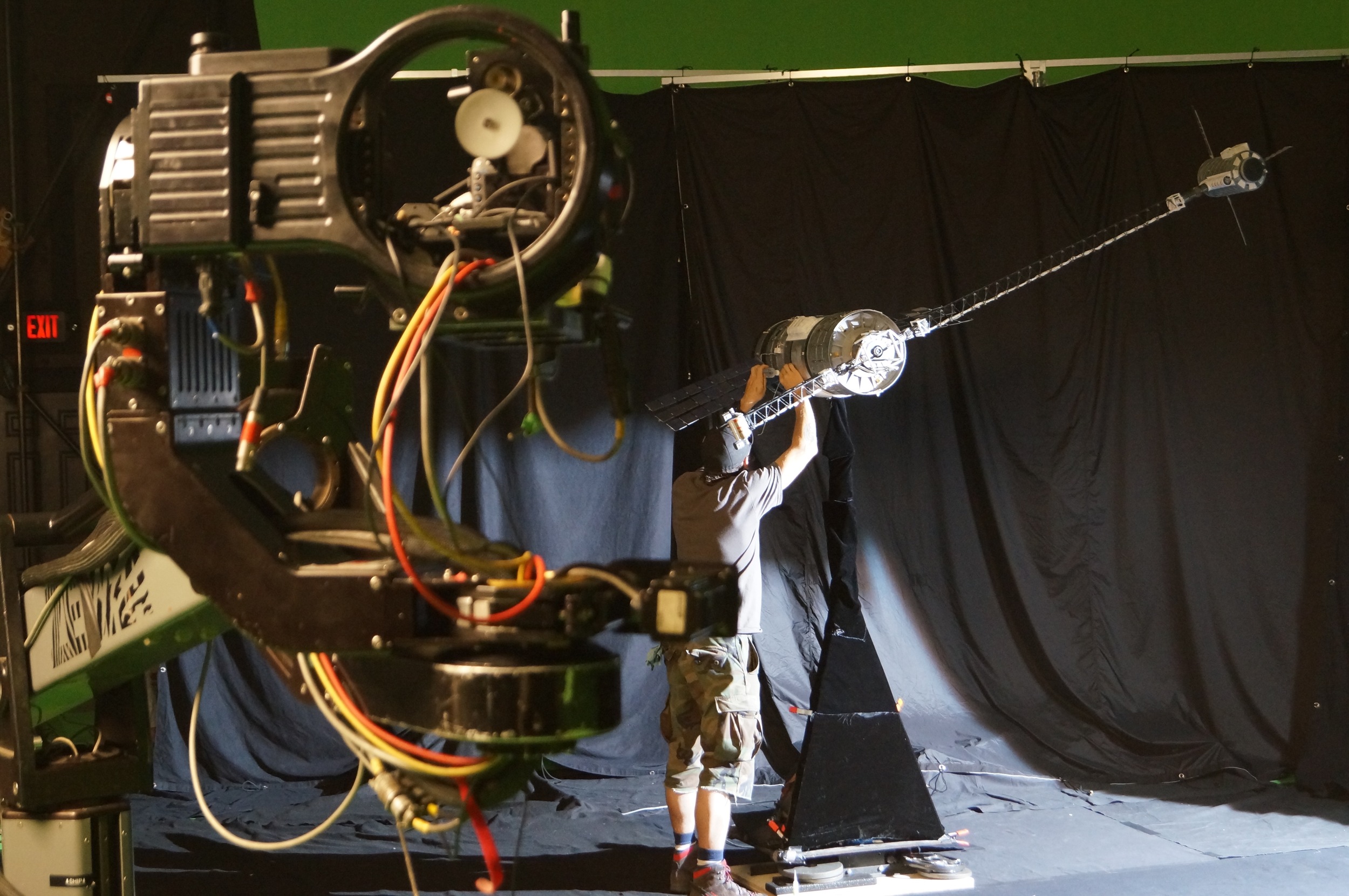

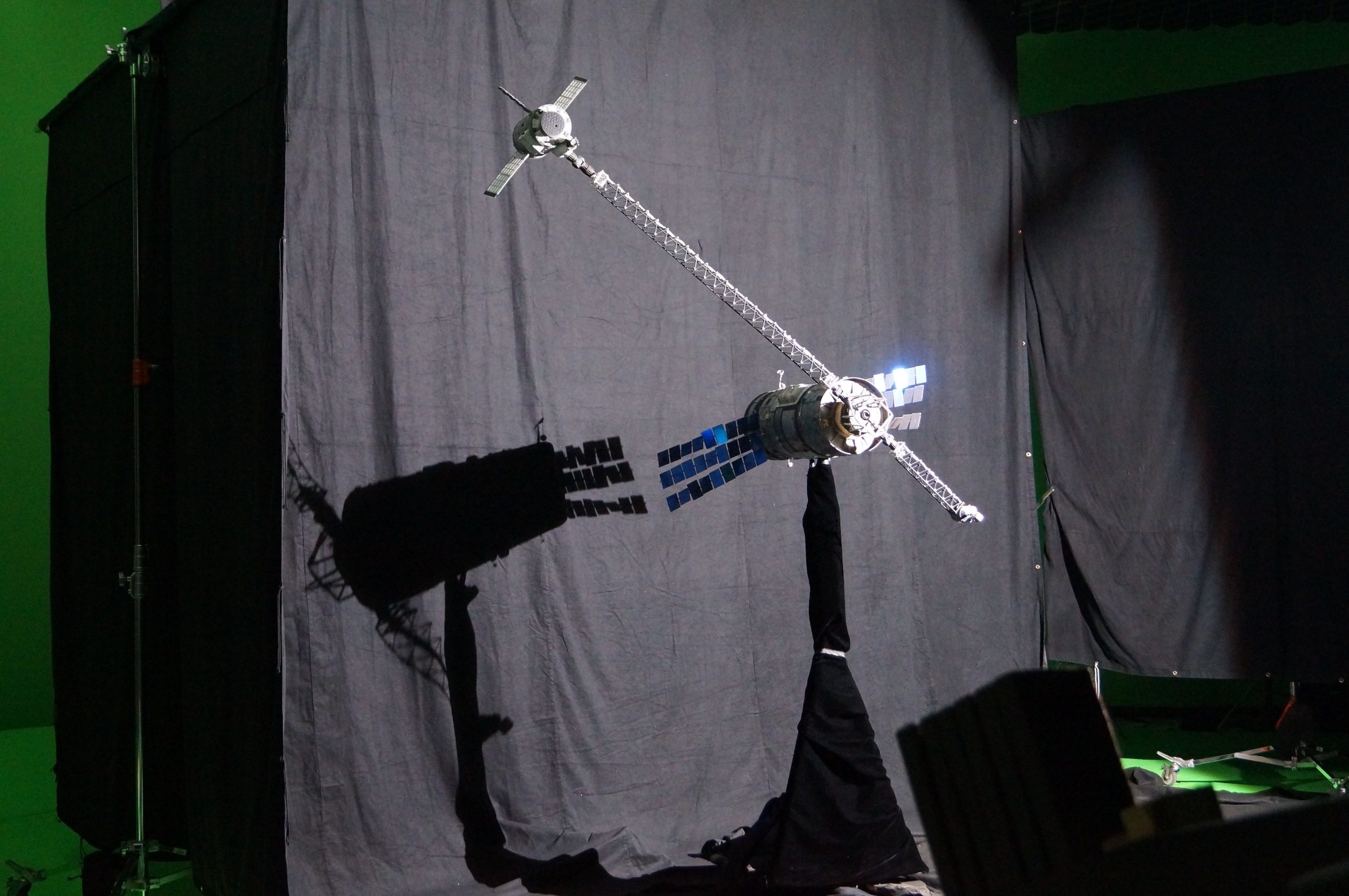

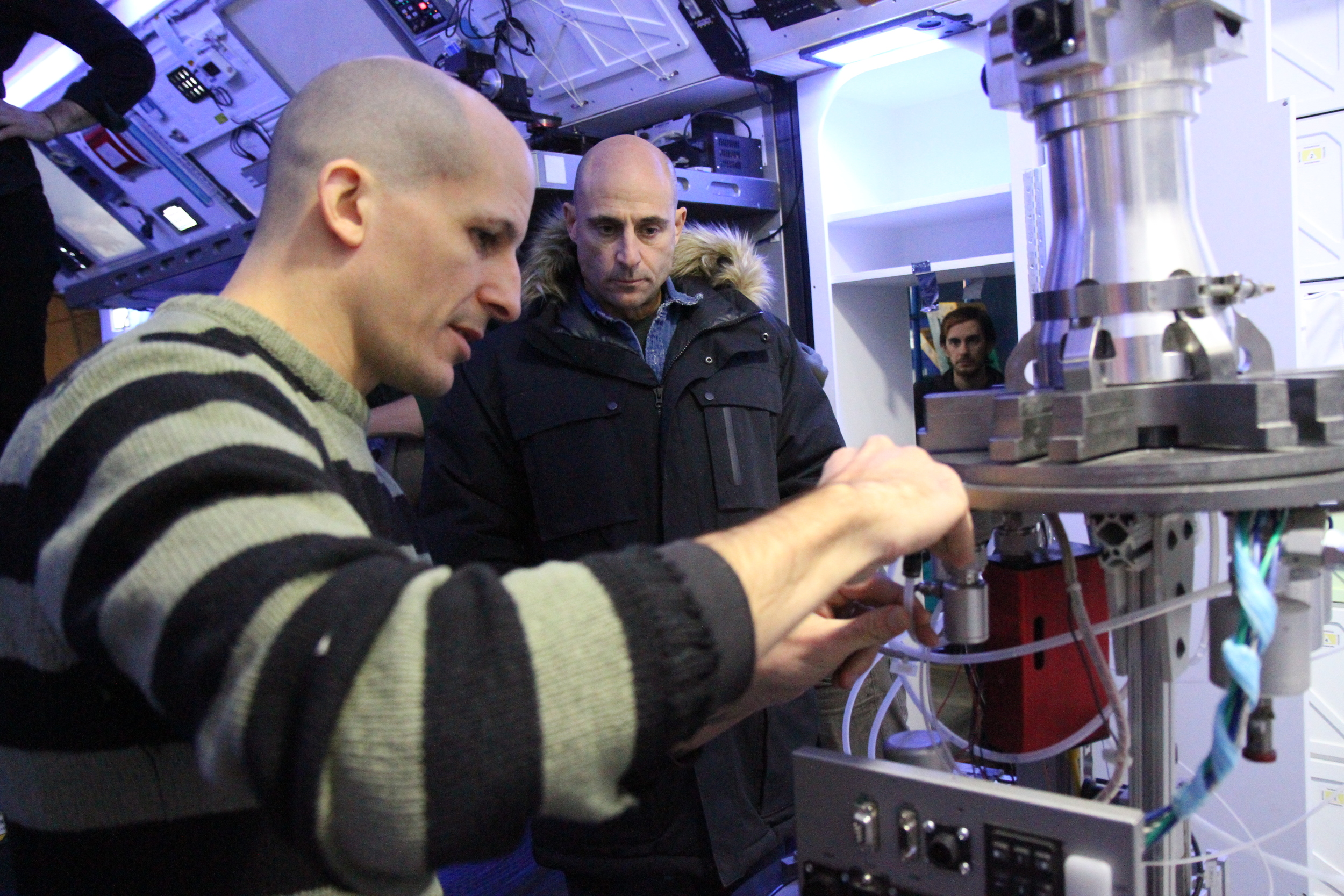

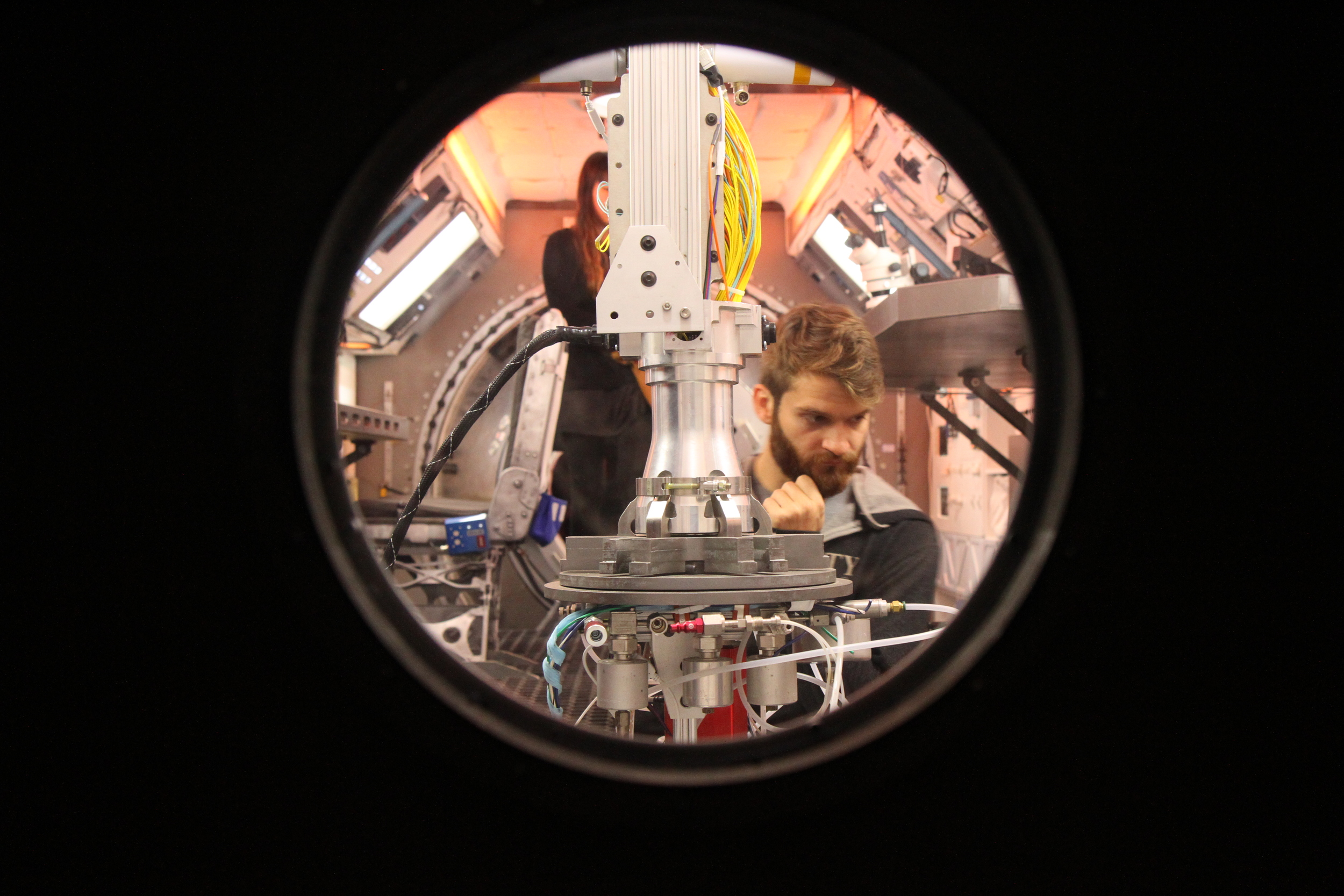

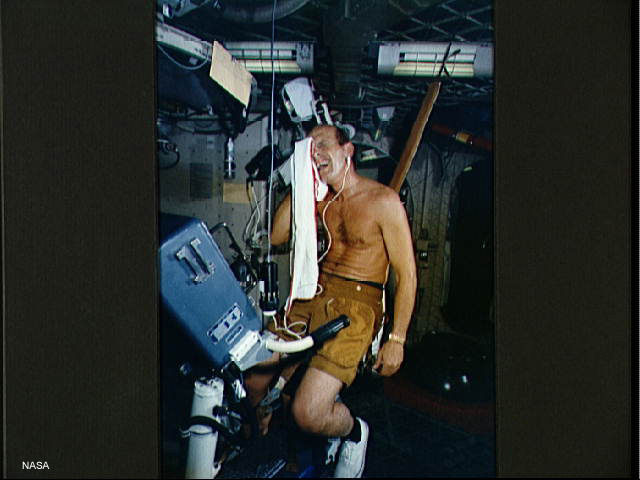

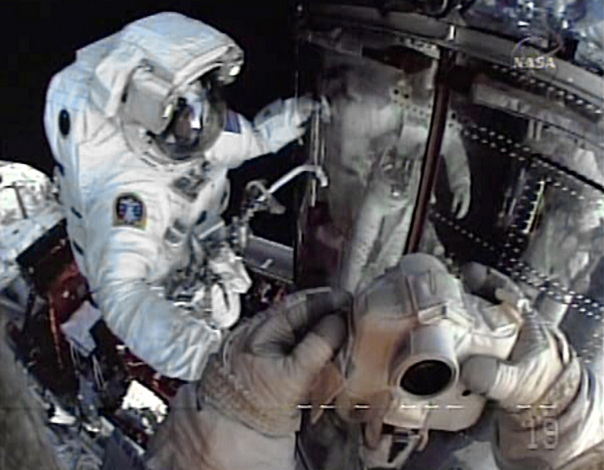

One of the biggest challenges of any long-distance space mission would be the effects on the human body of micro-gravity (experienced as weightlessness, floating), as your muscles would atrophy, your bones weaken, and disorientation and nausea could be ongoing concerns. We used a centrifugal force of a rotating arm of the ship to simulate gravity, which not only gave the ship some dynamic motion in the exterior shots, but allowed us to create a sequence where the gravity fails, a crucial emotional moment for the character to experience something unique and wondrous.

Communication delays would, with current technology, be a difficult challenge for any mission deep in space. You can make a cell phone call from New York to Tokyo, with the information beamed to satellites orbiting high above Earth, and hardly hear a delay. But the delay in communication between Earth and Mars could be up to 24 minutes--that’s how far away Mars is! That’s how long it takes light to travel between the planets. But scientists around the world are working on technology that could move particles faster than the speed of light, and the concepts surrounding quantum entanglement (wherein two particles react in simultaneous synchronicity despite being separated in space), provide the possibility for inter-planetary communication without delay. In the script, I toyed with the idea of having a long delay, which could have had interesting dramatic tension, but in the end decided that it was more dramatic if the mission began with perfect communication so it can be problematized later.

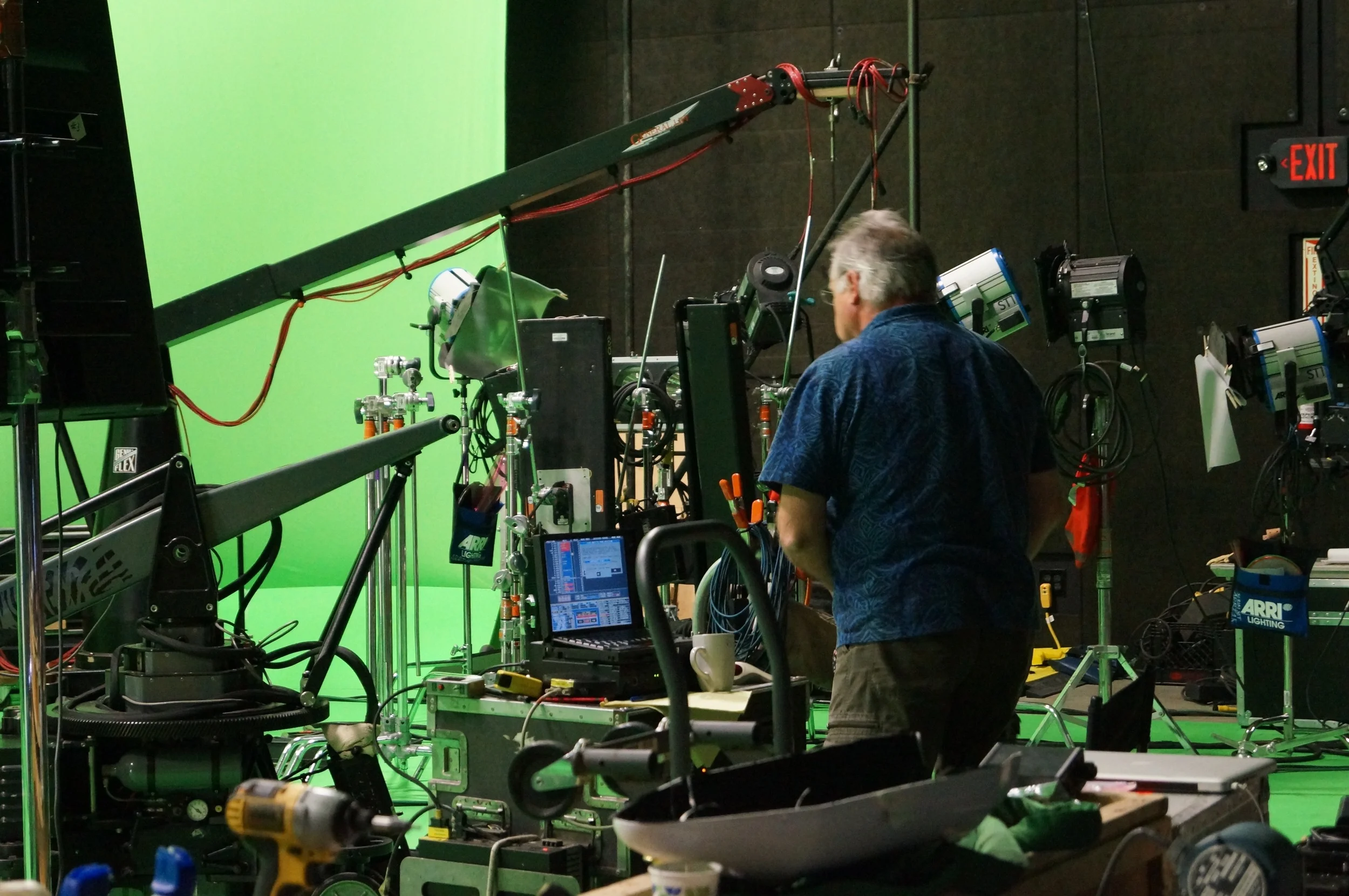

If you have questions about other scientific choices we made on the film, reach out to me. I’m happy to talk about it. I like to say, however, that everything that’s scientifically correct on the film is due to the incredible knowledge of our production designer, Steven Brower. Everything we got wrong is my fault.